By Paige Smith

A hand slams down on top of a Bible. “A-bom-in-ation!” belts out the preacher. We see his mouth wide, teeth white, skin black. His roared sermon is a warning. “Mankind shall not lie with mankind! For it is an abomination in his sight.” The devotees clap and cheer. Cut to extreme close-ups of Black men’s mouths with one proclaiming, “Priorities. That’s what I want to know. Come the final throwdown, what is he first? Black or gay?” The final thing heard in this montage of anonymous voices is from a Black family man: “Yeah man, like this AIDS shit. All the innocent victims, man. Mommas and babies dying, because of dope fiends and faggots.” Poet and activist Essex Hemphill cuts through these outcries, staring back into the camera lens, back at the audience. He listens to these painful stereotypes and declares in voiceover, “Silence is my cloak,” then whispers, “It smothers.”

This vigorous montage comes from Marlon Riggs’ radical 1989 documentary, Tongues Untied, which was released at the height of the AIDS crisis. Only a handful of years before, the disease was still being referred to as GRID, or “gay-related immune deficiency.” And even after scientific knowledge of AIDS was identified, fear and bigotry remained widespread. This anxiety caused gay men to be isolated, dehumanized, and violently harassed. Seeing familiar faces erupt with hateful words was a common part of life. Gay men became the new untouchables. When Marlon Riggs surrendered his film to this world, he was already an esteemed documentary filmmaker whose work pushed the aesthetic boundaries of what non-fiction could look and sound like. He was a Black gay man whose work as an academic, gay rights activist and filmmaker focused on representations of race and sexuality in America, and the ramifications of such depictions.

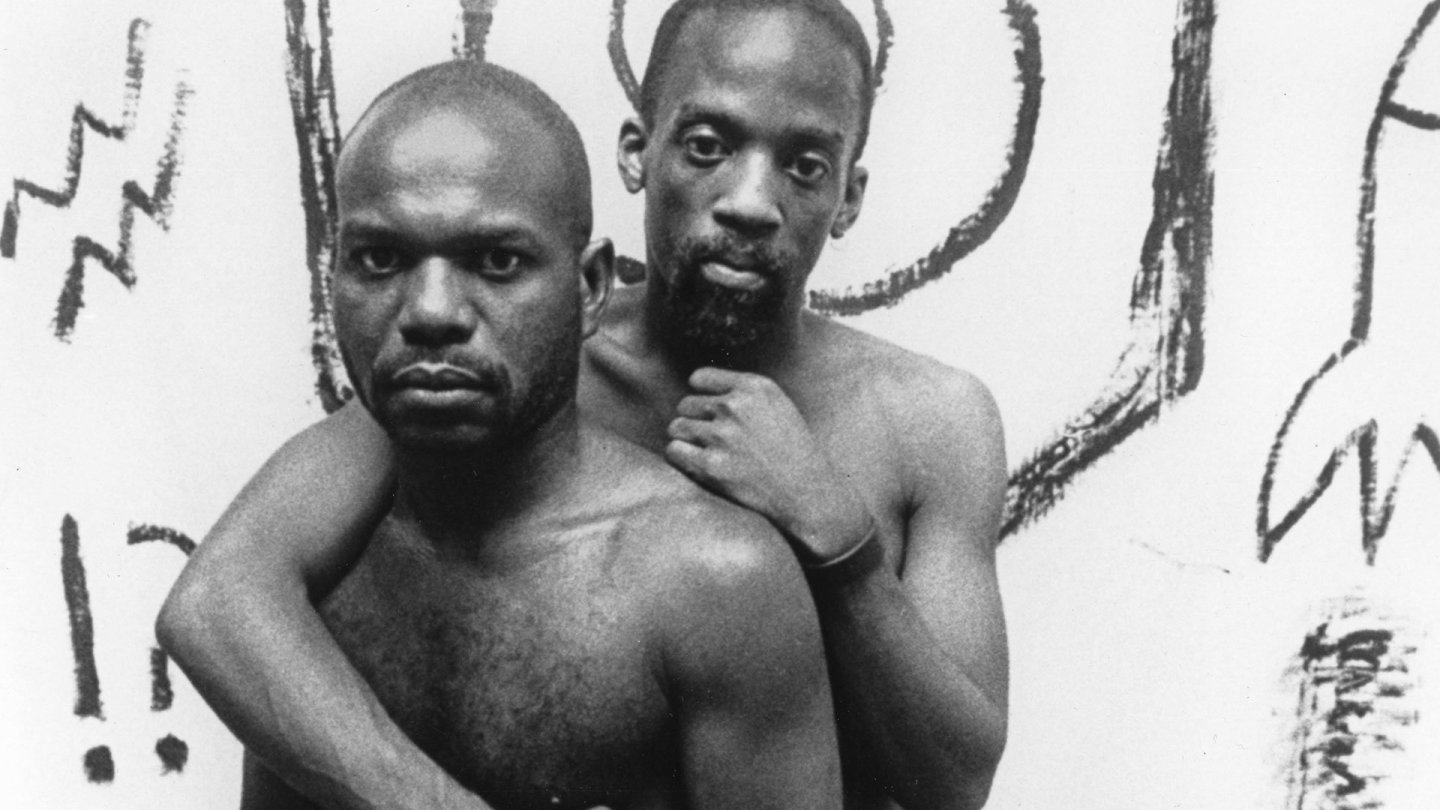

Tongues Untied explores how bigotry from the Black and gay communities affected the self-image of these men. Riggs features stories from his own childhood alongside those of a variety of other Black gay men. He tells these stories through an array of traditionally queer and Black forms, synthesizing these two styles to create a film that reflects his own intersectional identity. Riggs jumps between spoken word poetry, vogue dancing, snap!thology, a capella singing, protest chanting, fictional phone sex lines for Black activists, and re-creations of Black men making love. He pushes past the societal pressures to remain silent, and unties his brothers’ tongues so that they may all see their own beauty.

Riggs resists the hateful imagery of gay Black men from 1989 popular culture by depicting this community’s stories through their own words and cultural forms. Early on in the film, Riggs introduces The Institute of Snap!thology, a group of gay Black men that specialize in snapping as a form of communication. A slow-motion shot of one of these specialists provides an example of the Medusa Snap!. A bass plucks along to the beat. A man’s dreadlocks fly as he snaps his fingers together. The sound of a car crash accentuates his snap. They explain that snaps can be used “to read,” snap! “To punctuate,” snap! “To cut like a whip,” snap!

Rhythm is key throughout the film. Every moment is like drumbeat that creates a hypnotizing, syncopated cadence. (“Precision, pacing, placement, poise. A sophisticated snap is more than just noise.”) Riggs uses rhythm to lay bare what is hidden in the dangerous silence that poet Essex Hemphill speaks of. The collaboration between Riggs and Hemphill connects this extravaganza of performances. Hemphill’s highly rhythmic, jazz-influenced poetry and performance guide the viewer as Riggs’ brilliant editing bounces along to the beat. In every moment, Riggs is snapping into vision the stories of gay Black men that need to be uttered and heard.

As the film progresses, Riggs recounts his entrance into the gay community. He speaks directly to camera about being surrounded by white gay men. A chant, “Let me touch it, let me taste it, let me lick it,” is sung over images of gay pride parades filled with white male bodies. Through more powerful poetry, Riggs explains the absence of Black gay imagery, and how the few images that were popular at the time are deeply racist. A pornographic image shows a Black man in a metal collar and link chain being held down by a white man. It is titled, “Slaves for sale.” This kind of imagery causes painful self-effacement. Riggs explains how he avoided eye contact with other Black men on the streets, searching instead for his reflection in the love and affirmation of white faces.

The Black community wouldn’t welcome Riggs because of his queerness, and the gay community wouldn’t accept him because of his Blackness. His identity left him with no positive representations. Riggs remained silent not just for his own safety, but for his own sanity. If he were to be heard for his whole self, he would have to face either homophobia or racism from his peers. In an act of radical expression, Riggs makes visible what he imagines an ideal future would be for Black gay men. He combats systems of oppression to stop the self-hatred that many marginalized people face. He imagines such a history, where Black gay activists can find harmonious lovers and aren’t ostracized from both communities. A man calls into “Black Chat,” the aforementioned fictional sex line, to find that special someone, and leaves a voicemail about himself:

“B.G.A. Black gay activist. Thirty-ish, well read, sensitive, pro-feminist. Seeks same for envelope licking, flyer distribution, banner assembly, demonstration companion, dialogical theorizing, good times and hot safe sex.”

He twirls his fingers around the cord phone, his “Silence = Death” t-shirt hanging over the couch. He refuses to remain silent. Not just because silence is killing people through AIDS, but because silence is killing gay and Black people from the inside out. Riggs embodies the fears, the anger, the passions, and the power of Black gay men. He allows himself and his collaborators to express their unique experiences, just as the film breaks free from tired, traditional forms of documentary. Tongues Untied, like a song, is able to whisk its audience away into an understanding they don’t consciously process, but instead feel. Our bodies sync with the rhythm of the film. We look into the eyes of Riggs, of Hemphill, and of many others. Their vulnerability should not be dismissed or wasted.

Tongues Untied screens on Saturday, February 1st at The Cinematheque. For our own Black History Month programming, click here.

1 comment