By Josh Cabrita

In a recent Op-Ed for The New York Times, Martin Scorsese clarified his earlier dismissal of Marvel Studio products as “not cinema” (or so the grabby, context-free quote goes) and further derided them for being “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted, and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” Scorsese argues that when we watch a CGI blockbuster we aren’t coming into contact with the proclivities of an individual person but with the calculated decisions of executives. And if cinema is “about revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation,” then this style of production lacks something essential to it: “the unifying vision of an individual artist,” or in other words, an individual artist capable of revealing their aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual dimensions through their creations.

Movies help us overcome the fundamental solipsism of our subjectivity, and via Art’s mechanism of revealing, come into contact with the experience of another. This is a fanciful, downright romantic idea, and to see a version of it at play in Scorsese’s films, we only need to look as far as Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), the protagonist from Taxi Driver. In that film’s most famous scene, Travis stands in front of a mirror, alone, asking himself, “Are you talking to me?” While speaking to himself as he would another, Travis (“God’s lonely man”) confronts the limitations of his consciousness: who, if anyone, is listening?

This same question could be asked of Ace, the mobster from Casino, Henry Hill, the wiseguy from GoodFellas, and the rest of Scorsese’s yakking gangsters. It’s clear that their perverse behaviour is the result of a harsh affliction: alienated, they consider only their most immediate desires, hoarding money, snorting speed, and whacking whomever they see fit. But what is the aloneness—startling, suffocating, lacerating aloneness—that they feel? The Prophet Isaiah provides ample material for speculation:

“Your iniquities have separated you from your God;

And your sins have hidden His face from you, so that He will not hear.

For your hands are defiled with blood,

And your fingers with iniquity;

Your lips have spoken lies,

Your tongue has muttered perversity.”

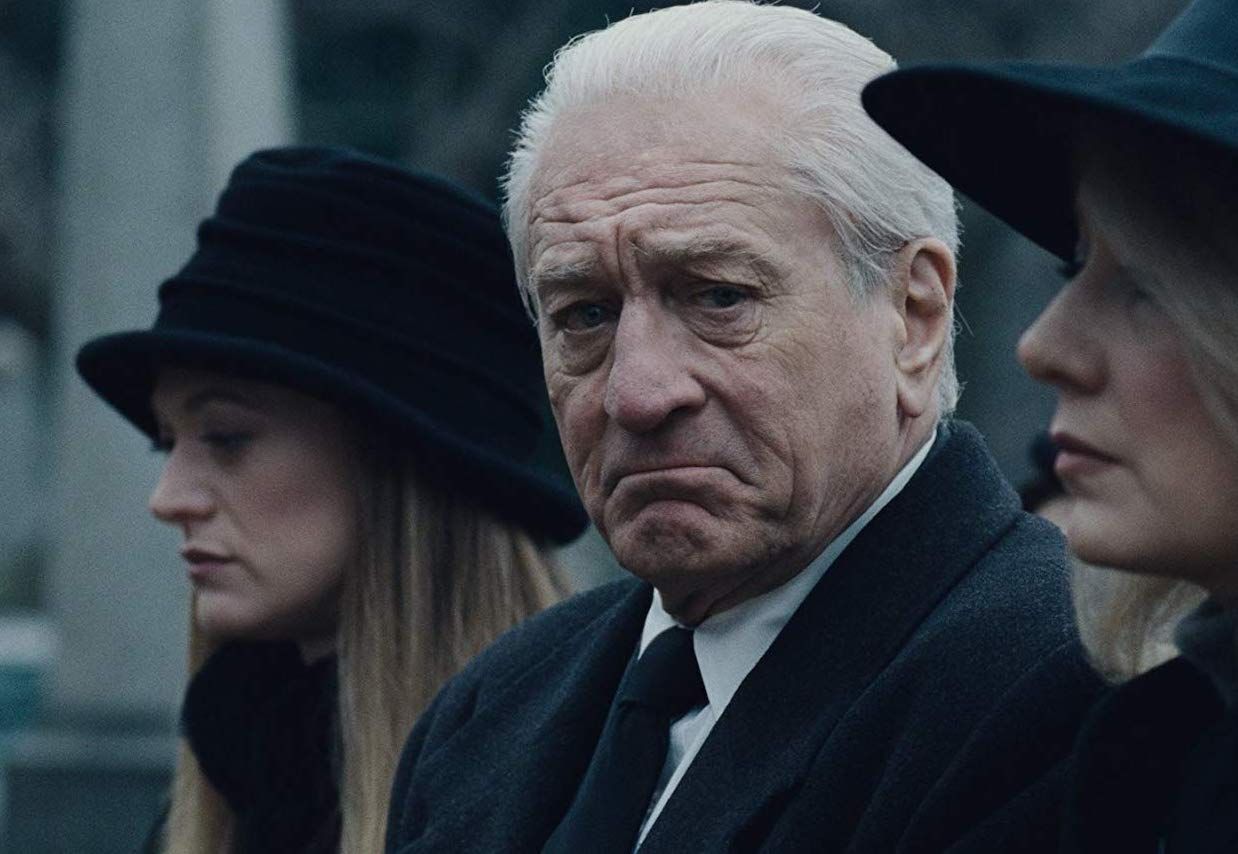

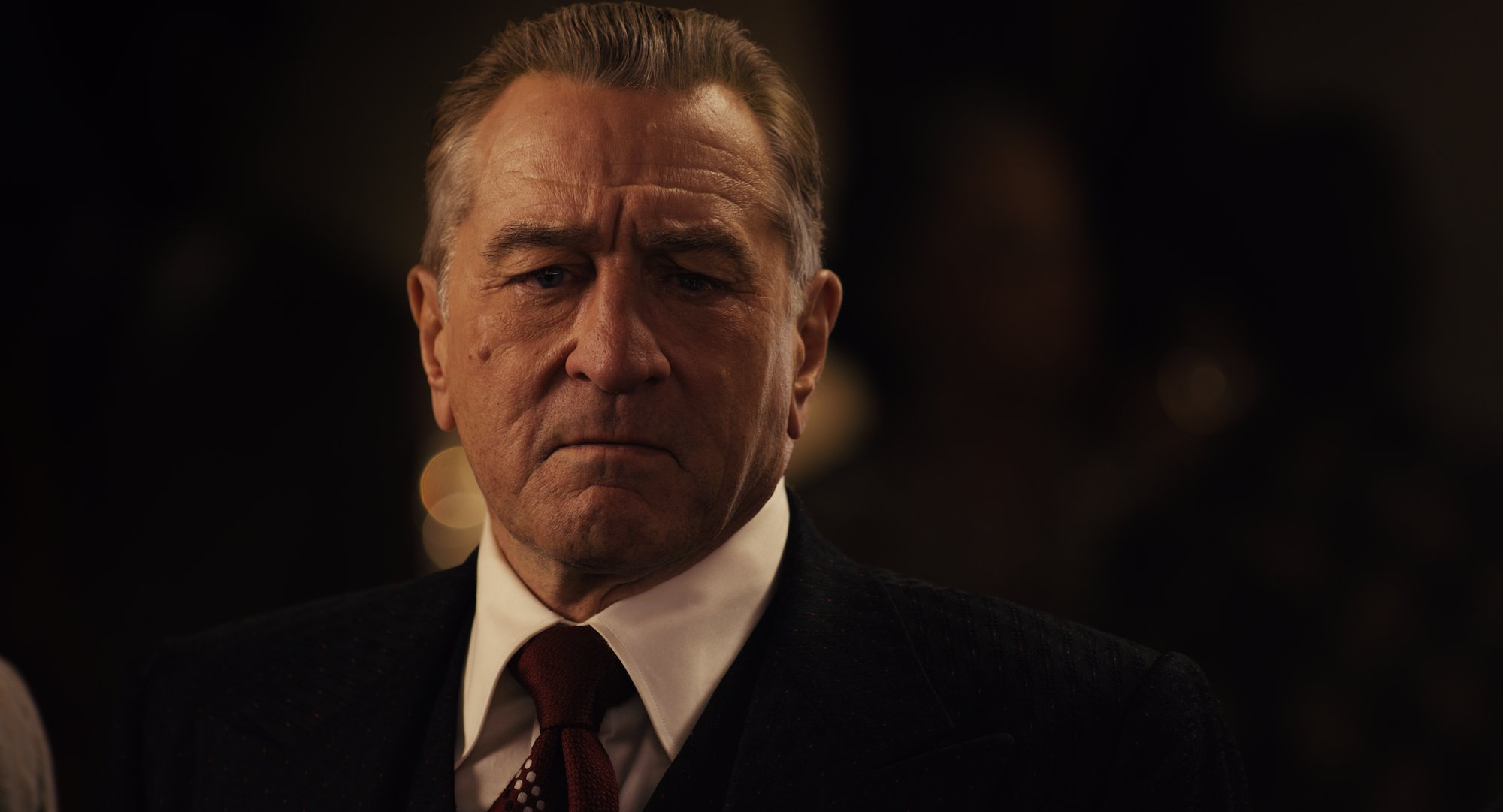

Hands defiled with blood, lips that have spoken lies, a tongue that has muttered perversity—all of these things describe Frank Sheeran (Rober De Niro), the protagonist of Scorsese’s latest gangster epic, The Irishman. Based on Charles Brandt’s true-crime book I Heard You Paint Houses, Scorsese’s film chronicles 50 years in American political life from the perspective of Frank, a lowly truck driver who becomes the assistant of Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), the Teamsters Union president who, for decades immediately following WWII, wielded his political power as ruthlessly as Frank his gun. Frank’s stratospheric rise during this time comes in large part to his association with Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), a delegate of the Sicilian Mafia, who had a mutually beneficial, though increasingly tense, relationship with Hoffa.

The Irishman differs from Mean Streets, Goodfellas, and Casino—all gangster stories set in a fallen Catholic milieu, told through the blinkered, hyper-subjective perspectives of their protagonists—for its piercing moral awareness. Frank narrates from his wheelchair and reflects on—say, confesses for—a life of incalculable evils. He relates his past glories in two separate timelines: in the earlier one, we follow his rise in the Mafia and Teamsters; in the later one, Frank and Russell drive with their wives to Detroit for the wedding of a mutual acquaintance. As the first story shuttles through years at a breakneck pace, the second takes its slow, methodical time, portentously approaching a moral reckoning that Frank clearly cannot bear to reveal but in the most roundabout, equivocal of ways.

The question of Frank’s remorse is nowhere more present than in how the film depicts his daughter, Peggy (Anna Paquin). There when he breaks a grocer’s hand for a mild offense, there when he observes the TV news of a killing he committed, and there when he sins a sin he is never to rectify, she is this film’s structuring absence, its moral centre, and her hovering, condemnatory presence doesn’t so much evoke a person in and of herself, but an angel of death, bearing witness to and calculating Frank’s misdeeds. But are these self-pitying remembrances of Peggy not a device for Frank to clear his conscience, for him to engage solely with himself and not truly bear the consequences of his actions on another? Do these recollections, which try and fail to view things objectively, constitute—to borrow the words of a priest from the film upon hearing Frank’s remorseless confession—”an act of the will”? Or is he, like the Scorsese characters of yore, still talking to himself?

What’s arguably so radical about The Irishman is that it arrives at a definitive answer to these questions: while meeting with a priest in his old age, stammering and adrift, Frank says to himself, and to the complete confusion of the priest, “What kind of person makes a phone call like that?” Those who have seen the film can attest to the force of this line’s impact, but suffice it to say that this constitutes a real, empathetic, wrenching confession—arguably the only one in the director’s gangster films. This scene completely reverses how these movies usually operate. Unable to rectify our own beliefs with those of Scorsese’s gangsters, we bring our own moral framework to Mean Streets, Goodfellas, and Casino. But in The Irishman, the moral framework comes already built in. Whereas Scorsese’s prior films maintained a tense push-pull between our distance and identification with the characters, this one manages an almost more impressive gambit: it makes us, whether we realize it or not, slowly associate with the increasing moral awareness of a murderer.

It’s Frank’s growing understanding of his misdeeds, and the viewer’s slow realization that their plight is ultimately not so different from his, that makes The Irishman so terrifying. In Scorsese’s other films, at least we had an escape hatch: if we assumed that sin is separation from God (as Isaiah says), and that separation from God is in turn the cause of these characters’ solipsism, then it also seemed possible that their ailments could be healed by grace and through faith. But The Irishman, like Scorsese’s last film, Silence, slowly reels us into agreement with its protagonist so that we can collectively confront the haunting ambiguity of this thing we call the sickness unto death: what if, upon our genuine profession of faith, there is no consolation—no radical grace, no cure for solipsism?

It’s no wonder that, when confronted with the eternal void, we return to what we know—and what Scorsese knows is cinema. If it once seemed possible that art could replace religion, The Irishman calls the longevity of this position into question. Just as the film chronicles the slow death of an economic system predicated on larger-than-life personalities, ritualistic codes of honour, and antiquated allegiances, so it also, on a more fundamental level, depicts the passing of a kind of cinema that, naively or not, put the individuality of the artist at the forefront. In the same way that the influence of the mafia was superseded by the hegemony of multinational companies, Hollywood has passed from a regime that privileged individual artists to one that has gradually and steadily eliminated risk altogether. With their wills taken away, how are filmmakers to confess? And worse yet, when they do—when they actually manage to lay down their most abominable and demented thoughts—who will be there to hear them?

1 comment