By Devan Scott and Will Ross

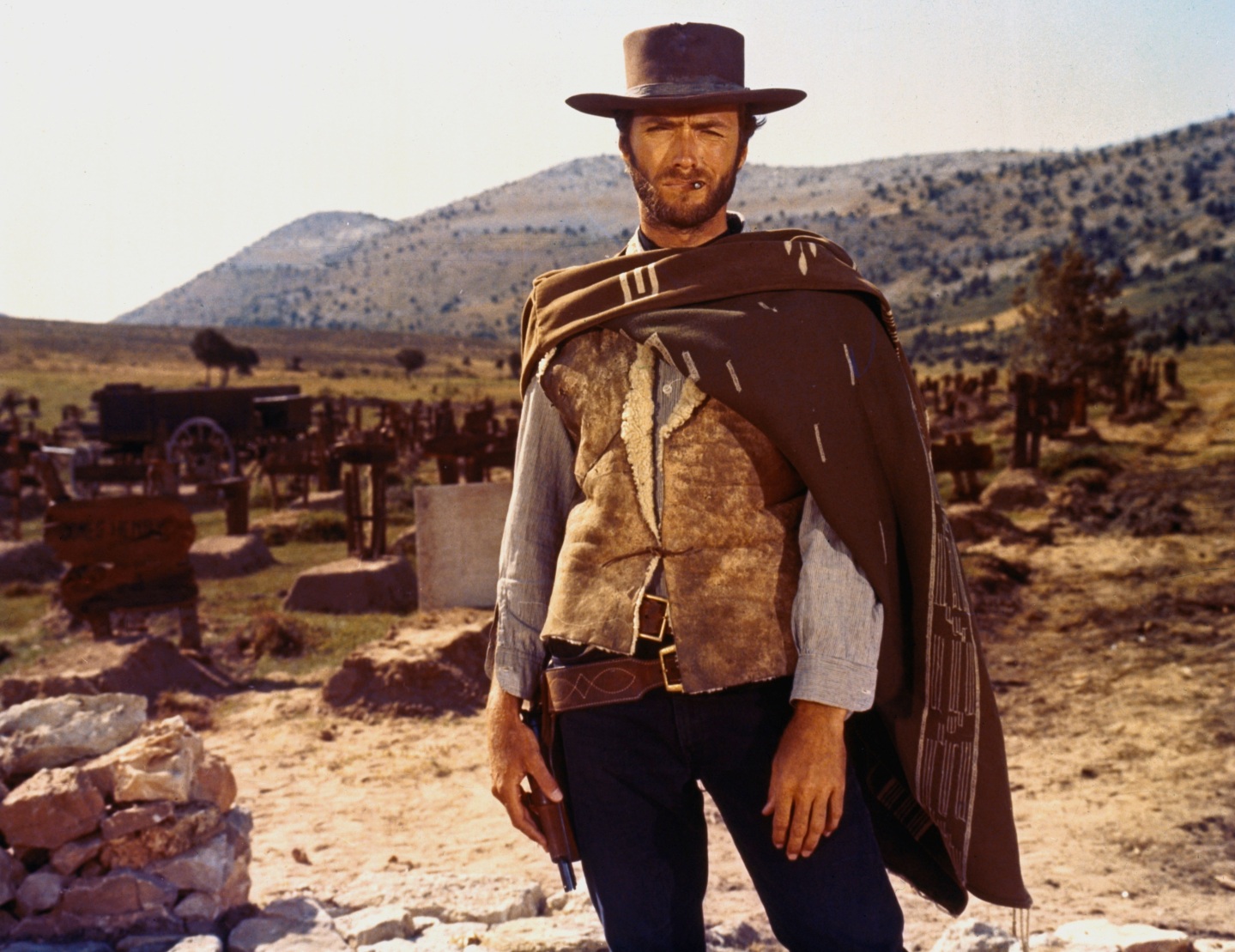

For the two of us — us being Devan Scott and Will Ross — the opportunity to show The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly at VIFF’s Vancity Theatre is a natural result of our long-held adoration for this most famous of all spaghetti westerns. Our presentation of this definitive cut comes after many years of research and debate, but more importantly it’s simply our latest act of devotion to a movie that has been formative for our own filmmaking sensibilities more most of our lives.

To explain the full extent of our love of this scrappy epic, we followed in the footsteps of Blondie, Tuco, and Angel Eyes and made our own pilgrimage to Sad Hill. In 2014, we traveled all the way to the middle of nowhere in the Castilla y León region of Spain to visit a small valley in the high plains of southern Burgos of little note.

Of little note, of course, but for a moment in the summer of 1965 Sergio Leone briefly transformed this valley into an otherworldly arena, the scenic capstone to his masterpiece The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. As such, we weren’t there to take in the (remarkable) landscape; we were there because of meaning imbued in the place by Leone’s camera-eye.

Leone constructed a dream-space, a world that transformed a historical setting into a space of elemental conflict. Sad Hill Cemetery is a place that does not feel like a real place, and in a sense, it isn’t one: nobody has ever been buried among those concentric circles of graves. Entering that space — or at least its literal geographical location — was perhaps the most deeply surreal experience of our lives, and we (along with our collaborator, Daniel Jeffery) did what any reasonable trio would do when confronted with such a space: we spent all day recreating the duel from The Good, The Bad and the Ugly shot-for-shot.

The Recreation

But the cemetery and surrounding area weren’t as they once were: the arid, desert-like fields and barren mountains were lush and green, the circular arena at the center was hidden under grass and weeds, and every grave’s tombstone was gone, now replaced by a bush growing over every mound of dirt. Sad Hill had changed; in the absence of human hands to tend to it, nature had taken its own course in preserving it.

It was an appropriate transformation for a film that similarly hasn’t stood still as long as we’ve known it. We each discovered the film as teenagers, entranced by the stylistic maximalism of its editing and its rollicking set pieces. There’s a reason an Italian-made export became an international hit, so iconic in its expression of Americana that its title has become a part of English vernacular, and it’s chock full of one-liners that ring with a brutal wit: “When you have to shoot, shoot, don’t talk,” “If you miss, you had better miss very well,” “There are two kinds of people in this world: those with loaded guns and those that dig.” The cinemascope framing, alternating between sweeping wide shots and granular close ups, contrasted the grandeur of an American landscape ravaged by the civil war with the gritty, desperate existence of the individual. In short, the stuff of a classic adventure story.

There may be no other foreign export that so entrenched itself as a piece of America’s self-image. As a result, it remains a gateway between pop culture and world cinema at large. Watching The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly today doesn’t just summon the memory of watching it as teenagers; it’s grown up with us. Time and scrutiny reveal the film’s more serious moral dimensions. As the film progresses, the American Civil War creeps from the background of the plot into the foreground. It insinuates itself subtly in the very first scene, the first set in a ghost town that’s been emptied out by enlistment and conscription in the Confederate army. Later it becomes unmissable, as the Northern and Southern armies slaughter each other pointlessly over an unwinnable bridge. Leone — who often insisted he was as horrified as he was fascinated by America — could not have been unaware of the US intervention in Vietnam as he crafted this battle. Its horrific results become impossible to ignore for Clint Eastwood’s character Blondie, who is silently moved by the waste of human life he begins to see at every turn. Blondie’s persona is the most unflappable of the three leads, yet he is given the film’s only perceptible arc, seen in gestures of mercy as seemingly trivial as lending a cigar to Tuco not long after the bandit tortures and nearly kills him.

That gift comes shortly after Blondie sees his rival in his most vulnerable and revealing moment, a reunion with his pious brother. Tuco, until this point, has functioned mostly within a standard archetype — arguably, a stereotype — of a Mexican bandit, granted a uniqueness and individuality mostly through the charismatic energy of Eli Wallach’s performance. Until the moment he excitedly greets his brother Pablo, Tuco has been an entertaining but irredeemably cruel figure, but in this scene he is emotionally broken. Rather than reciprocating Tuco’s warm greeting, Pablo coldly informs him that both their parents have died and tells him to leave; his bandit brother denounces him as arrogant and cowardly, and the two briefly come to blows before Tuco leaves in tears. It’s moments later, when Tuco lies to Blondie that he and his brother have a loving, affectionate relationship, that the cigar is offered and he is allowed to save face. For a film that has until that moment centered on vindictive one-upping between its characters, it’s a startling moment of shading for each man through the different storytelling means of personal gestures and a recontextualizing backstory. Tuco is a man who expresses himself in words, and Blondie through actions, and Leone ensures that the film expresses each one’s depth on his own terms.

Such development and reshuffling of the audience’s sympathies are peppered throughout. Yet for as much of the film is at once a dense, sinewy adventure, a rigorously researched evocation of its historical setting, and a stealthy character study, it is, as we mentioned, a poetic space that takes on an almost fairy-tale quality. Much has been written about the film’s use of space, the way that characters are often incapable of seeing things outside the camera’s frame. The technique suggests a storybook world that only exists within its own confines. The texture and authenticity of Leone’s vision of America gives it a palpable immediacy that legitimizes its political dimension; at the same time, its dream logic affords it the timelessness of a moral fable.

We may never come closer to stepping into that fable than when we stepped into the valley which, for the sake of a story, Leone and his crew one summer declared an ersatz cemetery. The place has undergone more changes since our visit, and now fans have fully restored it to its on-film appearance. The film is similarly due for an official overhaul: neither of Leone’s personally supervised and sanctioned cuts of the movie have ever received a home video release, with each new edition presenting new oversights and shortcomings while the film’s fans find their advice ignored and are forced to content themselves with privately-prepared reconstructions.

Yet the film continues its magnetic pull on us. When the two of us met, our shared love of Leone’s culminating work was one of the bases for our friendship and, eventually, our collaboration — it’s no coincidence that our filmmaking outfit, Sad Hill Media, took its name from the climax. Call it an obsession if you like; for us, a pilgrimage to the cemetery and recreation of its famous duel is a proportionate response. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly has occupied a place in our collective imagination for over 50 years; it seemed only appropriate that we spend some time occupying it for a change.

Sad Hill With Sad Hill doc

Join us for “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – The Definitive Cut” on Tuesday July 9th at 6:30pm at Vancity Theatre.